Carving Stone at Sculpture Camp: Paradise Among My People

Highway 46 weaves sinuously among the rolling green foothills; the drive between Cambria and Paso Robles ⅔ of the way down California’s coast is one of the most beautiful, soothing, and satisfying stretches of road I’ve driven thanks to those undulating forms. And yet all I could think about was how to refine their slopes.

Rolling hills along highway 46 by photographer Alexander S. Kunz; used with permission. See more of his work at www.alex-kunz.com

I was on my way back from sculpture camp where I’d been carving, filing, and sanding stone sculpture for nearly eight hours each day, so you’ll have to forgive me for still being in the mindset of coaxing my will onto forms so similar to those I’d been focused on for a week.

The landscape-like marble sculpture I worked on this week, still at the ‘lots of refining needed’ stage.

It took a while for me to even realize that I was imagining using steel hand tools to re-shape the landscape around me, and when I did I had to smile, albeit sadly. The transition back into ‘normal life’ had begun after my brief escape into a sculptor's paradise. The California Sculptors Symposium takes place mid-April each year at Camp Ocean Pines in Cambria. Days are filled with hours and hours spent working on sculpture, broken up only by instruction in different media and delicious meals made for you and spent in companionship with other artists. Evenings feature talks, slideshows, sunsets, games, and music.

It’s hard to communicate how valuable the experience is to me. I love my ‘normal’ life, don’t get me wrong, and it would clearly be too physically and mentally demanding for me to live each week working as intensely as I did this past one. But oh, the pleasure of having a whole day devoted only to shaping materials to suit my own vision. It feels deliciously self-indulgent, but amidst a life peppered with helping and serving others it’s essential to at least devote some time to serving only yourself.

This year was the first time I fully indulged; in the past I’ve taught at the event, which nonetheless leaves lots of time for one’s own work. But this time I gifted myself the whole time free of responsibilities. That is to say, free other than the usual tether of checking in on my family, which was notably a little different this time since one of my sons just got his nose broken in a soccer game the day before I left. Grandma and Grandpa helped even more than usual at home in my absence with doctor visits and follow-up. But other than phoning in to his ear/nose/throat consultation and extra attention to my device alerting me to anything (cursing each time I had to take off the layers of protection on my face and hands only to find a spam message or special offer) I had no other demands on my time and attention.

Protecting eyes, ears, lungs, hair, and hands makes for a lot of layers to remove when checking the phone…

You may have noticed that I primarily work in fiber, by the way. And sculptural needle felting is indeed the topic I have taught at camp. But I also love other materials and methods of making, and there are things I’m just not really set up to do at my own studio. CSS began primarily focused on stone stuclpture, but it also offers other media that changes by the year, and the Board of Directors bring in different instructors who excel in their fields and teach particularly well.

This year attendees had the option of working with Jason Arkles of ‘The Sculptor’s Funeral’ Podcast fame, who teaches the nearly-lost Renaissance technique of sculpting from life using the ‘Sight-Size’ method. Some opted to spend half of their days practicing figure sculpture from a live model. Jason is an excellent instructor who’s also living the dream with a huge studio in Florence, which he only leaves to come teach some lucky students a few times each year.

Jason (bearded, in the apron, center left) in action at the 2022 workshop. Somehow I didn’t get a photo this year.

Alex Yoshikawa of Splady Art Studios in Oakland taught students all about sculpting in wax, which acts as a proxy for bronze: in lost-wax casting, an original object is made in wax (or multiple copies of an object can be made by pouring wax into a mold) and then a hard ceramic-like shell is used to coat the form, with special attachments used to form channels into and out of the sculpture. That wax is then melted out, and the hollow left behind is filled with molten bronze. Here’s a video I made long ago about the process. It’s pretty incredible, and Alex is highly skilled and experienced. He and Chuck Splady are masters of working with metal- and besides making their own sculpture they also help other artists realize their visions. They are the ones who fabricated the frame-like structures that suspend my ‘Hanging Pods’. They also teach classes in hot and cold ways to shape metal, so reach out if you’re interested.

Alex (on the left), Chuck Splady (center) and my own kid a few years ago at Splady Studios. You know, showing a nine-year-old how to do some plasma cutting!

Oakland-based Ibiza-born artist Marcel Regueiro led the group of stone sculptors in tool use, finishing techniques, and modeling an understated dry wit in one’s approach to banging on a rock until you get the shape you want. His journey as a sculptor- literally a journey that took him from Ibiza to London to Vermont to Oakland- is an entertaining lesson in deciding what you want and working to accomplish it, assisted by a strong sense of self and sense of humor.

Finally, I can’t help but mention the unofficial instructor in all things sculpture-related, Stephanie Robison. She’s a gifted, innovative, incredibly hard-working sculptor (you’ve got to check out her latest work that combines stone and felt) but on top of that she’s one of the best teachers of anything I’ve ever known. She welcomes in a student at whatever level of skill and knowledge they currently have, and she makes sure they know the safe, smart, effective way to use tools and materials-- the how and the why. And she’s patient and generous with her knowledge without fail. She’s the one who recruited me for the camp in the first place, and is responsible for bringing in over half of the warm bodies attending this year. She teaches at CCSF, and if you’ve ever wanted to learn sculpture she’s the one you want to learn from.

Marcel Regueiro with Stephanie Robison, on the field, of course.

Let me paint you a picture of my experience last week. I decided to spend my time and energy carving stone, since 1) it’s different from what I usually do 2) it’s uniquely pleasurable, 3) I don’t normally have access to all of the specialized tools and 4) it’s not something I’m really set up to do at home because it’s loud and messy.

The large field overlooking the ocean is transformed to workspaces by laying down tarps (to catch the bits of stone that go flying so we don’t leave them for kids to stumble on), erecting pop-up tents (because even on the coast the sun will burn you), and arranging work tables (portable and pretty good, but they still move a bit when you’re hitting at heavy rocks perched atop them). I was in the ‘beginner tent’ area where I could share tools and benefit from the roving instructor’s nearness, while the returning carvers set up their own stations around the field, some with power tools.

The stone sculpting field, from my 2022 visit. The ocean is that vast expanse to the right over the trees.

Dangers of stone carving come in the form of flying rock chips, dust, loud sounds, and missing with the hammer or rasp- so goggles, masks, ear protection, and gloves are the outfits of choice. And hair covering, since stone dust makes one’s hair turn into straw until the next shower.

Stones can be acquired through a silent auction on the first morning: alabaster, marble, soapstone, and a few other varieties that come from donations from personal stashes. There’s also a representative from Art City in Ventura who often has larger stones. Note: a week is not a very long time to work on a large stone, but you can take it home to finish. But small also has its drawbacks-- a lot more clamping and using sandbags to hold it in place. Last year I carved a fairly small piece of marble into a form similar to one I’d made in wood, and although I finished it while there, I do recall the fussiness of having to keep it in place as I worked.

My smallish stone in progress from last year (next to the carved wood piece I modeled it on), wedged in place with a wooden clamp since it was so small and lightweight.

I came to the camp with a stone I bought at last year’s auction-- a piece of marble that had a hole drilled through it. I was intrigued by that piercing, and determined to make use of it. The piece reminded me somewhat of a bone (I collect them and love the sculptural form and function of anatomy) and I wanted to incorporate both hard and soft, much as I’ve done in felt with my Flesh & Bone series.

My chunk of marble in the ‘Before’ phase laying on a sandbag, with my hammer, chisels, and paintbrush for dusting away bits.

I also put some bids on stones in the silent auction, and secured a rounded, flat piece of alabaster that looked like it will be a bit translucent when finished- intriguing and beautiful. Alabaster is much softer than marble, as I would come to find out. But first I tackled the marble piece.

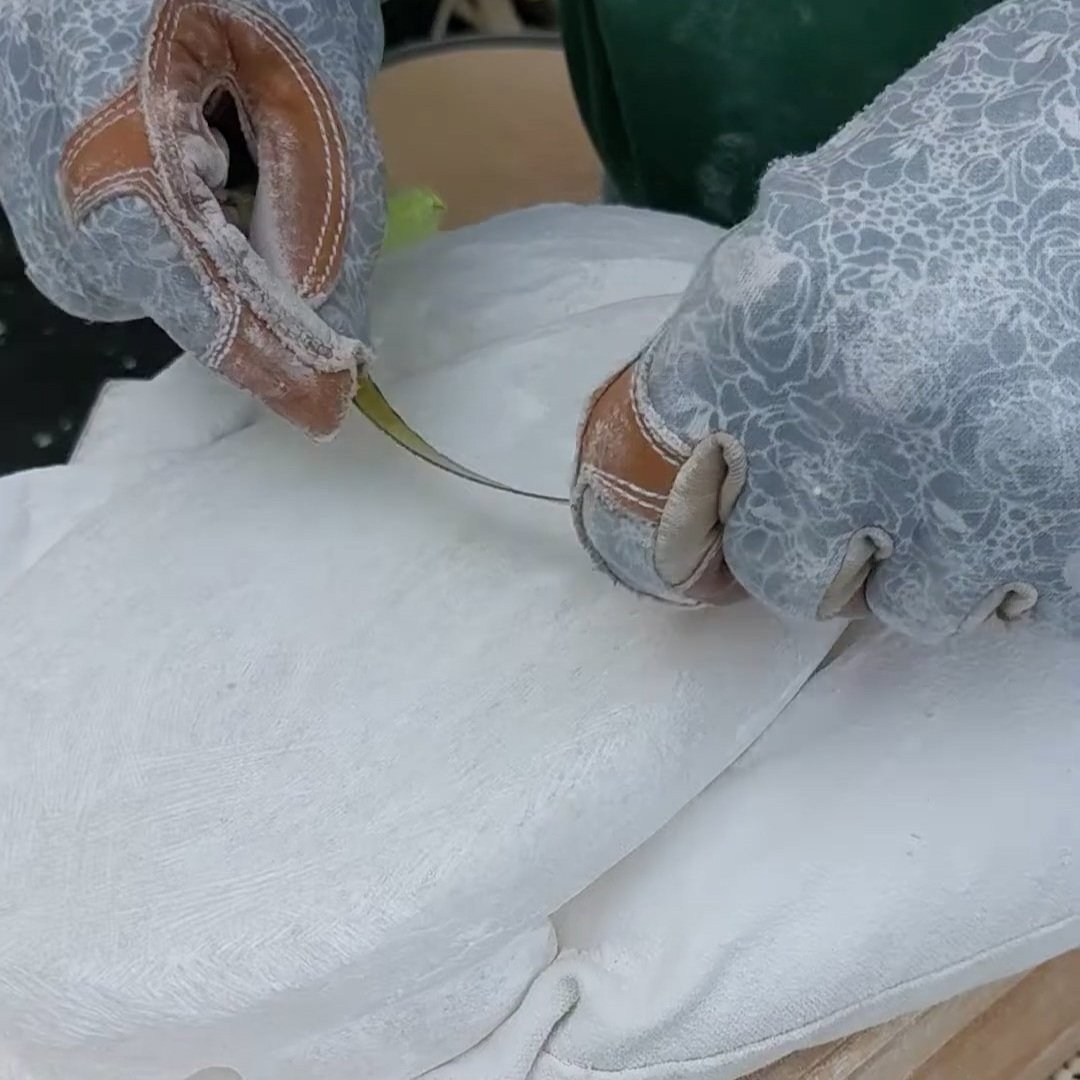

I have some experience with stone carving; in college I took a week-long workshop with Kazutaka Uchida while still at the University of Oregon, and the hammer and chisels I bought back then still, of course, work. There are plenty of other tools for specialized and generalized use, however, and CSS is the perfect opportunity to try them. Learning about new tools to use- or old tools to use in different ways, like a hacksaw blade as a means to scrape smooth, even curves (below)-- is satisfying and challenging.

Using an old hacksaw blade held in a bowed shape can give you a nice scraper for curved areas. Who knew?

But I’m getting ahead of myself. I started by using a hammer and chisel, although depending on one’s stone and design there is also cause to use power tools to drill or cut off parts of the stone. There’s no cheating in stone carving, just different tools for different goals. Chisels can be pointed, rounded, flat, and shaped like rakes, all of which have their uses. Understanding the angle needed for the best use of force is key to effective hand use, as is correcting one’s body and hand positioning to avoid injury.

The marble had some cut marks in it already, which helped inform my design— even though one of my goals was to obliterate them. I started with a clawed chisel.

As I mentioned, I’ve carved before AND I had a sense of the form I wanted, so I drew on some outlines in colored pencil and just went to it. My stone was large and heavy enough that I could position it on a sandbag and it didn’t need to be clamped in place, which meant that I could turn it over and around as needed without having to pause and re-clamp. Yet it wasn’t so large and heavy that it took a lot of strength to move it around-- I really hit the sweet spot and avoided a lot of the ‘friction’ of dealing with the stone itself, which let me move from area to area as needed. The first day I roughed out my form pretty well, and slept well that night after such a workout. I’m used to repetitive arm motions, but the added weight of the hammer is certainly different than needle felting!

You can faintly see the red pencil marks I used as a guide, and the way I’ve worked my way across the surfaces with a small flat chisel at this stage.

A note on where you sleep at camp: there are cabins with bunkbeds that can hold 10 people- but we grownups occupy them at a rate of only three or four to a cabin, and each cabin has its own shower room and toilet/sink room. It’s rustic but works well, and the water’s hot. Some people choose to stay offsite in hotels or vacation rentals, but I like the full camp experience, I must admit. Not that I have a photo for you.

Over the next several days I used rasps, abrasive grinding bits, diamond riffler files, and these amazing scraper tools modeled on ones found in stone carving sites from the Renaissance, if the stories are true.

Using a triangle file to work on shaping those curves.

It’s kind of crazy to note that simple pieces of steel can shape hard stones- at least when applied with a lot of care and patience. Other participants are incredibly generous in sharing and lending their tools, which requires that one be equally generous in not stealing them even though said tools are not made anymore. Sigh.

Using a simple but incredibly effective scraping tool, which I can’t find anywhere to purchase! Tell me if you have a source! Please!

I took a break from my marble piece when I’d gotten it pretty far to address the lovely alabaster. Here's where I left off. If you look closely you’ll see a faint red circle around a bruise I’ll need to tackle.

Still in need of sanding, but almost there!

Carving alabaster is quite different from carving marble. From Marcel I learned that very little hammer and chisel work should be used in favor of rasps, since alabaster is softer and far more bruisable and breakable than marble. Bruising a stone, by the way, is what happens when you crush the crystal structure, leaving a white dot that requires a lot of scraping or sanding to remove. So my second stone was an exercise in wearing away at the surface rather than breaking it off.

A diamond rasp was a good (if laborious) way to take down some of the surface without danger of leaving bruises that would show later.

At some points what I was doing with a scraper in one hand and a paintbrush in the other felt akin to archeology: digging gently and carefully, and brushing away dust to see what was revealed.

Using the scraper to start to define the outlines of where smaller foreground forms meet the background shape.

It was, in a way, meditative- but I was also eager and a little impatient to get to my form. I conceived of a grouping of egg-like pods that would (hopefully) be even more intriguing in their finished translucent appearance. A lesson on finishing a stone began with addressing the importance of not rushing to the sanding stage. Sanding over scratches or white bruise marks doesn’t remove them; instead one has to scrape or abrade down to remove them and only then is sanding appropriate. So I had to slow down again and remind myself that sanding, at least, I can do at home.

Roughed out but still a ways to go. Luckily the finishing is fairly satisfying.

By the end of the week I was extremely pleased with my progress on two different pieces, although I had a hard time tearing myself away from working on them. Part of that was the sheer satisfaction in smoothing and refining those elegant slopes and clean edges; part of it was my acknowledgment that it truly is difficult for me to find time to work on ‘extra’ things once back in my regular life. I guess it’s about ‘carving’ out time and space to do what you find agreeable and worthwhile- pun clearly intended.

‘Agreeable and worthwhile.’ I wonder how many people in the general population would describe stone carving (or other means of sculpting) in that way. Besides the actual act of making art, the real value in sculpture camp for me is being among other people who share that outlook. As a working artist it often feels like I have to explain the value of what I do in terms of money, time, and energy resources. I have to try to put into words why art is necessary to humankind; heck, I have to start with asserting that it even IS necessary. Art has to be framed as a commodity that others will buy; my worth as an artist has to be determined by whether and how much other people pay me for what I do. I know that’s not true, but it’s a pervasive ongoing demon lurking around the edges.

Among my fellow sculptors there’s simply the accepted fact that shaping materials feels good on so many levels. That doesn’t mean it’s easy or simple, just that it’s important when you’re wired like us. It feels like a deep, slow sigh to breathe out all the reasons and inhale the sweet shared air of doing and being and making for its own sake.

And to share that life-giving oxygen with generous, funny, thoughtful, open-minded people was the real treasure of sculpture camp. The personal connections you forge while deeply engaged in creative pursuits among kindred spirits is something I need- we all need- in our lives. It’s another thing I get to bring home from camp with me.

Until next year, CSS tribe!